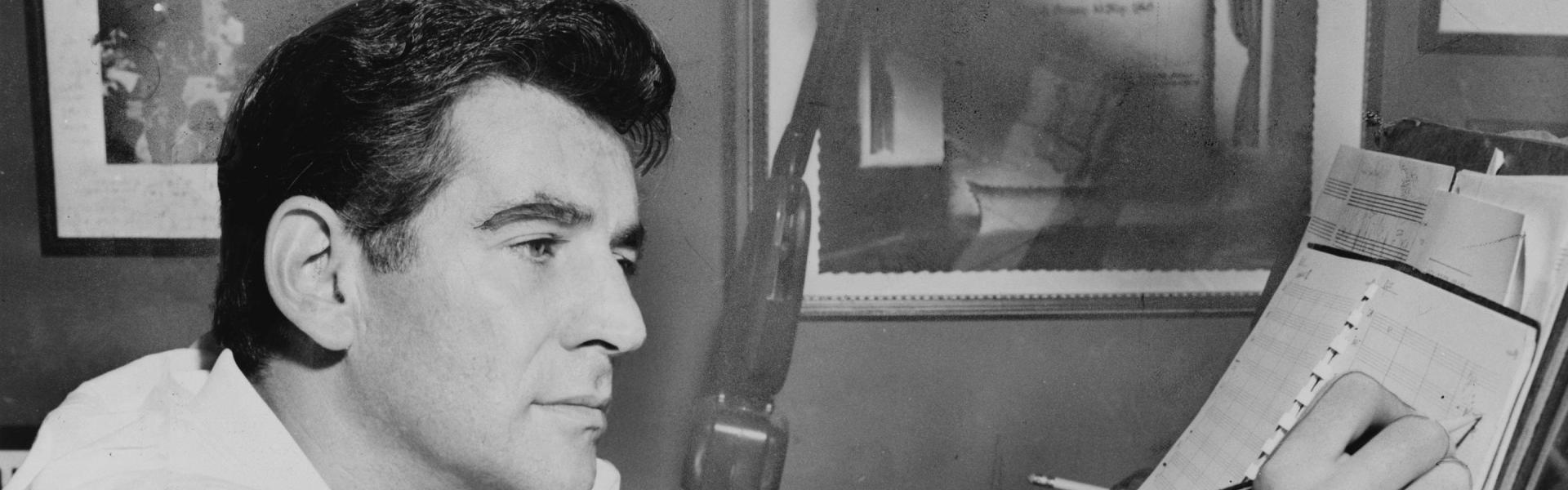

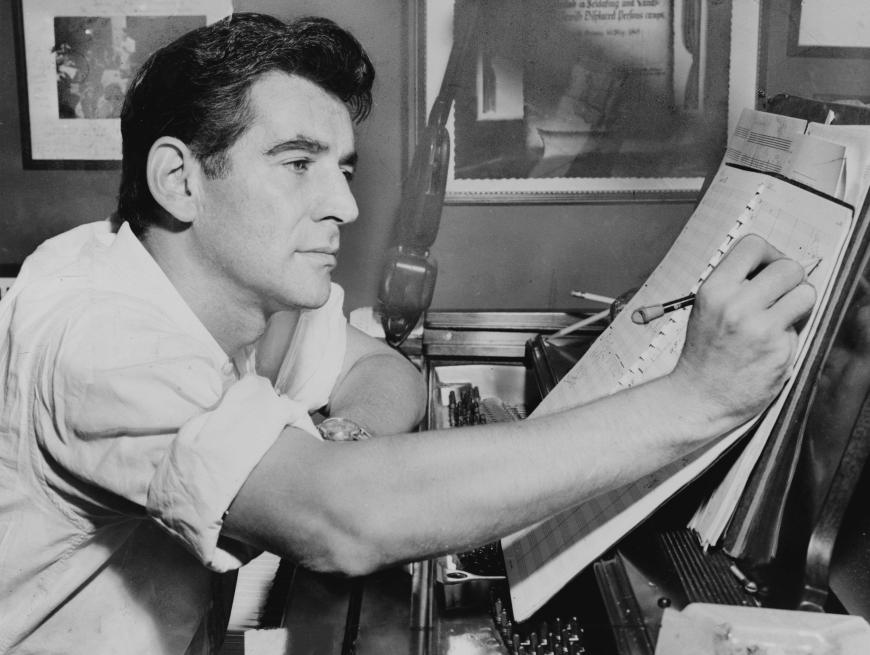

More than three decades after his death, Leonard Bernstein remains a vital force in the classical music world — something you can’t say for the other superstar conductors of his era. (Been to any Eugene Ormandy festivals recently?) The reasons for this are many.

His ebullient personality, captured so often on television broadcasts, translates well to streaming platforms. While his status as a composer remains controversial, his best works touch audiences in a way few of his contemporaries can match. His proclivity to integrate pop sounds into compositions such as his Mass was largely derided in his day, but now seems ahead of its time.

Moreover, his interpretations of the classics are distinctive and inspired, inviting repeated rehearings. A larger-than-life figure in his day, his time in the spotlight has yet to run out, even though the “Bernstein Century” (the grandiose label attached to Sony’s reissue of his recordings in the late 1990s) is long past.

Picking his greatest or most essential recordings is an impossible task. He made so many, and their quality is so consistently high, that any fan could easily come up with a credible list without creating much overlap. The most obvious selections, like the suites drawn from Aaron Copland’s ballet scores, George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris, the Beethoven Violin Concerto with Isaac Stern, Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf coupled with Camille Saint-Saens’s Carnival of the Animals, Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 88, and the Mahler symphony cycles, among others, remain bestsellers and need no introduction. In this list, I highlight those that continue to strike particularly strong chords in me.

Haydn: The Creation; New York Philharmonic (Sony, 1966) or Bavarian Radio Symphony (DG, 1986)

Over the course of his career, Bernstein recorded much of the standard repertoire twice: With the New York Philharmonic in the 1960s, and again with a number of European orchestras in the 1980s. Aficionados argue endlessly online which version of a specific work is superior. Not surprisingly, the later recordings tend to be a bit slower and weightier, as he transitioned from Wunderkind to Old Master status.

This is quite evident in his two recordings of Haydn’s greatest oratorio, which were recorded in 1966 and 1986, respectively. The earlier recording is infectiously bouncy and spontaneous, while the second has a notably heavier, more portentous feel. With superb singers in each, choosing the better version is entirely subjective (and may even change from day to day).

Both provide evidence that, while he was best known for romantic and post-romantic-era repertoire, Bernstein was a superb Haydn conductor. True, his recordings sound nothing like the slimmed-down, period-instrument-influenced readings that dominate the scene today; as one critic put it, he viewed Haydn as “Beethoven’s older brother.” But he consistently captures what so many conductors miss: Haydn’s wit, joy, and playfulness.

Mahler: Symphony No. 9 Berlin Philharmonic (DG, 1979)

Contrary to legend, Bernstein didn’t “discover” Gustav Mahler, but he did place him right in the middle of the standard repertoire, where the composer remains today. Bernstein famously complained that other interpreters didn’t take the composer’s detailed instructions seriously enough, shaving down the music’s rough edges. Mahler, he argued, wanted his symphonies to encompass the entirety of our emotional lives, juxtaposing humor and heartbreak , solemnity and satire.

Some critics argue a less-is-more approach is preferable, and there’s no better way to contrast the two than to listen to the Ninth Symphonies of Bernstein and Pierre Boulez, the man who succeeded him as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Boulez’s approach is far from emotionally detached, but he lets the music unfold without a lot of fuss. Bernstein, in contrast, is all fuss — speeding up here, screeching to a near-halt there. It’s quite a ride.

Both men agree that the final movement is about death. But in Boulez’s relatively placid reading, death is a peaceful reunion with the natural world that Mahler loved so deeply. For Bernstein, it’s a terrifying encounter with the unknown. Both interpretations are valid, but Bernstein’s is the one that leaves you shaken to your core.

William Schuman: Symphony No. 3; Roy Harris: Symphony 3 New York Philharmonic (DG, 1985)

Bernstein was a Harvard undergraduate when Serge Koussevitsky and the Boston Symphony gave the world premiere of William Schuman’s Third Symphony in 1941. He wrote a rave review of the piece at the time, and later became the work’s foremost interpreter.

It’s no surprise that Bernstein brought particular vigor and insight into works of midcentury American composers. These were his peers and, often, friends, and he was determined to use their music to prove to the world that American composers were producing work equal to their European counterparts. The Third Symphonies of Harris and Schuman are persuasive examples, at least under his baton.

Both are assertive, muscular works — products of a culture that was flexing its muscles on the world stage. Bernstein gives them astonishing momentum, exuding both power and optimism — a national characteristic we would do well to reclaim.

Bernstein: Candide (DG, 1989)

Bernstein’s 1985 studio recording of West Side Story is a famous misfire. Cast with opera singers who didn’t really understand the Broadway aesthetic and couldn’t persuasively embody the characters, it is something of an embarrassment. But four years later — just a year before his death — Lenny recorded his other great musical theater work, Candide, and this time, the results are transcendent.

The music isn’t as lushly romantic as West Side (try the new movie soundtrack, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, for that), but its pastiche of various operetta styles is thrilling in its own way. Consistently witty and droll, it’s a high-spirited parody, a great work on its own terms, and a worthy musicalization of Voltaire’s cheerfully cynical novella.

Candide has been revised many times since its 1956 premiere, with numbers dropped and added for seemingly every revival (and new recording). This “final revised edition” (there were more to come) was skillfully assembled by conductor John Mauceri. The outstanding cast is led by Jerry Hadley and June Anderson, with none other than Bernstein’s old friend and collaborator Adolph Green as Dr. Pangloss. It’s also the recording that includes the most music — almost every song Bernstein wrote for the show.

Bernstein: Chichester Psalms, On the Waterfront, Three Dances from On the Town — Bournemouth Sinfonietta, Marin Alsop conductor (2003) (Naxos)

Marin Alsop is clearly the greatest living interpreter of the compositions of her one-time mentor, and this disc offers a superb sampler of Bernstein’s works for large orchestra. Typically for him, the origin stories of the three fine works on this disc are quite different. The brooding On the Waterfront, with its haunting horn solo, began life as a film score, but is strong enough to stand on its own in this concert suite. The dances from On the Town were, of course, adapted from music written for his first Broadway show.

Chichester Psalms, a sacred three-movement choral work with a Hebrew text, was written during a sabbatical year Bernstein took from his New York Philharmonic position. Short but substantial, it fluidly travels back and forth between exuberance and prayerful poignancy. Alsop gets her British musicians (the Bournemouth Symphony) to play in an authentic Bernsteinian style.

Omnibus (4 DVD set)

Baby boomers such as myself still have pleasant memories of Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts of the 1960s. But I have a particular fondness for his earlier television venture: Seven episodes of Omnibus, a Sunday afternoon program from the 1950s designed to teach cultural literacy, which he wrote and hosted.

Bernstein, with his usual enthusiasm, is coming to terms with a brand-new medium and trying to ascertain how it can be used to further appreciation for, and love of, music. His methods are, necessarily, low-tech, but they are also brilliant and effective.

Take the episode where he discusses Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The first page of the work is painted onto the floor of the soundstage where he (and, later, other musicians) are standing, giving his talk a striking visual component. He realized television was a unique medium, and he took advantage of what it could do.

Moreover, his enthusiasm and ability to communicate complex ideas without speaking down to anyone remains impressive all these decades later. Watching him discuss and perform some of the Beethoven’s discarded sketches — his early drafts of the symphony, in a sense — remains a fascinating, instructive experience.