The great conductor Seiji Ozawa, who died in February, once mentioned that he knew essentially no English when he arrived at Tanglewood to study with Pierre Monteux and Charles Munch. Ozawa’s prodigious memory and work ethic took care of the gap soon enough, but listening to his legacy of recordings, you get the sense he had no need for English to express himself.

As a Japanese person, born in China, who studied with great European and American conductors, Ozawa personified the universality of music. It is no accident that he considered conducting Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with an international orchestra at the opening of the 1998 Nagano Olympics one of his proudest moments. The broadcast audience heard a chorus performing in multiple locations around the world, linked via satellite and coordinated by a conductor who himself connected continents and traditions.

While Ozawa was a fanatic for the “letter of the score,” he was also a great accompanist and never would have said, as that tyrant of Olympus, Arturo Toscanini, supposedly did to an astonished diva, “When the sun comes out, the stars disappear.” Toscanini’s passion dominated his recordings; Ozawa’s passion was just as strong, yet listeners often can’t hear his personal imprint. On record especially, it was as if he disappeared in clouds at the summit.

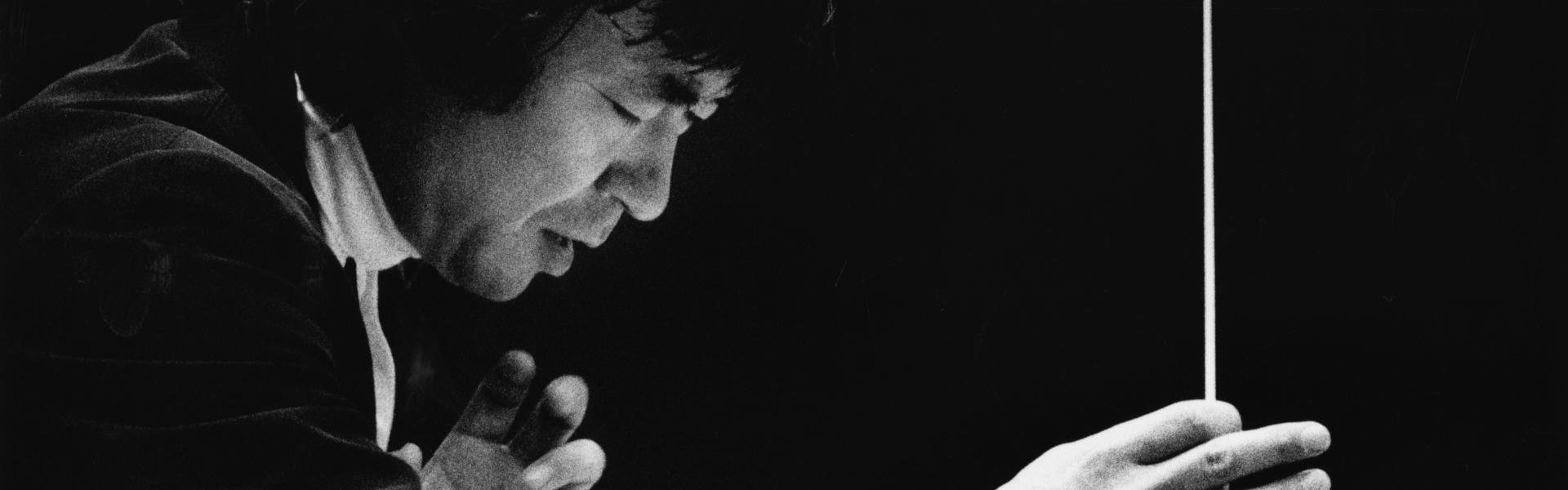

Possibly, Ozawa’s visual impact was so strong that he set expectations for a transcendent personality. He was more fascinating to watch than any other conductor this side of Leonard Bernstein, under whom Ozawa served as an assistant conductor. (But then, he also served under the mystically inert Herbert von Karajan.) He was his own ballet troupe on the podium, gracefully enacting the score with his pliant frame and his long hair, which did its own dance. It was as polished as his approach to music.

But his podium manner was not an act. His orchestras played with understanding, balance, and complete confidence. Finely graded color yielded clarity and detail. Some listeners grasp for a way to define his impact on the music, as if he were faceless. Others detect the opposite. Composer John Williams said that when Ozawa led the Boston Symphony in his music, he heard “textures lying deeply within it which I had not realized.”

Throughout his huge discography, Ozawa’s particular approach paid off in the biggest, densest scores, such as Charles Ives’s Symphony No. 4 and Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder. He was also at his reliable best with French composers, such as Hector Berlioz and Maurice Ravel. Here are a few of Ozawa’s finest recorded performances:

Tchaikovsky: Swan Lake — Boston Symphony (DG, 1979)

Because his orchestras sounded at ease and no phrase or tempo ever seemed forced, ballet was Ozawa’s great strength. His recording of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake is gracious and buoyant, enhanced by brilliant Boston Symphony soloists, not least concertmaster Joseph Silverstein, who shared the conductor’s unstressed, ecstatic elegance, as if this music were for a leaping heart as much as a tapping toe.

Respighi: Pini di Roma, Feste Romane, Fontane di Roma — Boston Symphony (DG, 1979)

Among the many large works Ozawa clarified were the three Roman tone poems by Ottorino Respighi. This recording is exciting, atmospheric, and powerful. The whole BSO is juicy, the brass dazzling, the strings transparent. Ozawa misses no detail, but no detail steals the show (unless, like me, you’re waiting with bated breath to hear Harold Wright’s shimmering clarinet solo in “The Pines of the Janiculum”).

Bartók: The Miraculous Mandarin Suite — Boston Symphony (DG, 1977)

Béla Bartók’s ballet The Miraculous Mandarin has color and flashy instrumental parts to spare. Even if the paprika here isn’t as strong as in some Hungarian recordings, the BSO is virtuosity incarnate. It plumbs the notes and the narrative. Trumpets and trombones gleam, winds dash, and together they float over luscious strings that purr and growl. (For the import LP version with Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, see this link.)

Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring — Chicago Symphony (RCA, 1968)

Ozawa’s 1968 recording of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring with the Chicago Symphony is a special case of a colorful ballet that benefits from a more “close-up” sound that RCA engineered. There is an extra level of energy, and the performance is by turns nasty and mellifluous. Even at swift tempos, the orchestra doesn’t sweat, but the music is pungent. The young conductor has every balance under tight control. Among performances of The Rite, this is still a standard recommendation, even though later recordings have more advanced sonics. André Previn effused over Ozawa’s interpretation: “Seiji should take out a patent on his Rite of Spring.”

Lutosławski: Concerto for Orchestra, Janáček: Sinfonietta — Chicago Symphony (EMI/Angel, 1971)

The Ozawa-Chicago partnership, representing the conductor’s 1960s stint at the Ravinia Festival, was also documented by EMI/Angel. Perhaps top of the heap is a disc (now in a Warner Classics collection) that couples Witold Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra and Leoš Janáček’s Sinfonietta. These are dream performances: committed, flowing, intense, intimidating, and they’re further documentation of Ozawa’s ability to be at once “both sophisticated and primal,” as the singer-songwriter James Taylor once described the conductor.

Messiaen: Turangalîla-Symphonie — Toronto Symphony (RCA, 1968)

Beyond his skills for digging into well-known repertoire, Ozawa’s partnerships with Toru Takemitsu and Olivier Messiaen were a productive constant in contemporary music. In this recording of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie, Ozawa is at his primal best but is also a spiritual musician. He later admitted that when conducting, “often, I feel I am praying.”

Olly Wilson: Sinfonia, John Harbison: Symphony No. 1 — Boston Symphony (New World Records, 1985)

Ozawa recorded an impressive range of American music, and these discs are essential because some are the only recordings of certain works, such as pieces by Roger Sessions and Peter Lieberson. Most worthwhile is this disc coupling John Harbison’s Symphony No. 1 and Olly Wilson’s Sinfonia. The opening of Harbison’s symphony has a familiar, romantic yet jazzy West Side Story feel. The passionate strings in Wilson’s second movement are reminiscent of Ozawa’s excellent recordings of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 9. And Wilson’s third movement is also home territory for Ozawa, redolent of The Rite of Spring.

Fauré: Pelléas et Mélisande, Dolly — Boston Symphony (DG, 1987)

Ozawa’s thoroughness at realizing rhythms, dynamics, colors, and balances was an obvious strength. His polish and detail could also project triumph, mystery, and sorrow, but bitterness wasn’t his strong suit. That’s another way of saying Ozawa couldn’t shake his youthful charm, and charm is what makes this single-disc collection of music by Gabriel Fauré an Ozawa essential. The delicacy and emotion are simply perfect, from playful to rapt. The orchestra shines, as does soprano Lorraine Hunt, and as a result, the music sparkles even more.