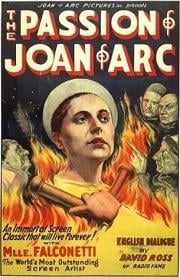

Illiterate teenage girl, transvestite mystic, military hero, condemned heretic, canonized saint — Joan of Arc was all of these. Her tale of triumphant conquest and pitiful suffering has fascinated historians and artists for centuries, and motivated Danish filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer's movie La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (The Passion of Joan of Arc), which has been hailed as one of the greatest cinematic masterpieces of the silent era. Great films deserve great scores to accompany them, and efforts to wed music to this film’s haunting images have spawned several hybrid creations in the decades following this film’s premiere. The history of this film and its music is as fascinating as it is convoluted, but, with Voices of Light, a 1998 composition by American composer Richard Einhorn, the timeless story of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc seems to have found its 21st-century voice.

Bay Area residents will have an opportunity to experience this hybrid of celluloid images and live music on Dec. 2, when the Pacific Film Archive, Oakland’s Paramount Theatre, and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival will offer a screening of Dreyer’s 1928 film. Dr. Mark Sumner will conduct a large ensemble playing Einhorn’s music during the screening of the film. Sumner will collaborate in this performance with tenor soloist Daniel Ebbers, baritone soloist Martin Bell, the University of California Alumni Chorus, the women of UC Berkeley’s Perfect Fifth, and the UC Men’s and Women’s Chorales.

Featured Video

Buy Tickets

Voices of Light/The Passion of Joan of Arc

Venue: Paramount TheatreCity: Oakland

Date: December 2, 2010 7:30 PM

Price Range: $25

Sumner could have chosen any of several extant scores for this exhibition. Since its first showing, Dreyer’s film has had the same sort of unstable relationship with music that most silent films experienced. Jacob Gade, the orchestra leader of Copenhagen’s Palads Teatret, first scored it for its 1928 premiere in that city, using a pastiche drawn from the orchestra’s library of familiar classics. A critical success, the film was exported to France, where it received a more lavish treatment, with original music by Léo Pouget and Victor Alix, orchestrated by Eugène Météhen. The reels contained a note to exhibitors that this score was “obligatory during the screening of the film”, and the score accompanied the movie to the U.S.

For a long time, the use of this score in its original version would have been impossible. Just a few months after the film’s first screenings, the negatives and all prints of the original film were destroyed in a warehouse fire. Dreyer reconstructed the film from his original workprints, but, in an incredible stroke of misfortune, this reconstruction, too, was destroyed by fire. Dreyer then abandoned any hope of recuperating his project.

In 1952, French film historian Lo Duca created a new sound version of the movie, combining multiple secondary cuts with a newly compiled score consisting of music by Albinoni, Bach, Vivaldi, and Scarlatti. Dreyer was as horrified by the new score as he was by the mottled visual results. Writing to the head of the French distribution company, he griped, “Believe me: the silence of the silent version would make a much better impression for the public than the violent fortissimo of the chosen music [in Duca’s version].”

Buried Treasure

In 1981, the film received a new lease on life when a virtually complete print of the original film was discovered in a storage closet in a Norwegian mental institution. New exhibitions — and new scores — were commissioned. Danish composer Ole Schmidt provided new music in 1983, and two new orchestrations of the original score were written in 1985. Dutch composer Jo Van den Booren composed another new score in the same year, and French composer Arnaud Petit created an ambitious computer-assisted soundscape for the Ensemble Intercontemporain at IRCAM, the famous center for new music in Paris. Other, more recent scores have been prepared by singer/songwriter Cat Power, Norwegian electronic group Ugress, and composers Jesper Kyd, Tõnu Kõrvits, Bronius Kutavičius, and George Sarah.

Of all the new music associated with this film, Einhorn’s choral work, Voices of Light, has received the most acclaim. His piece was chosen to accompany the 1999 DVD release by the Criterion Collection, and it was a Billboard chart topper in its guise as a CD issued by Sony Classics in 1995.

According to the composer, the work was directly inspired by Dreyer’s film. It was obviously composed with dual film exhibition and live performance in mind, but Einhorn is quick to point out that the work is not dependent on the film, but is a self-standing piece of music.

Even on its own, the work is a hybrid. Einhorn calls it “neither opera or oratorio, but a mixture of both.” His musical language is distinctly modern, yet thoroughly tonal. It is clearly influenced by the sound worlds of minimalist composers, but it also strives for long-scale development. Repeated themes and careful orchestration give the whole score a climactic arc reminiscent of big Romantic pieces. Einhorn also takes his libretto from medieval sources: He blends religious ecstatic texts by Hildegard of Bingen and other female mystics with harshly misogynist secular poetry and the words of Joan of Arc herself. The result is a dizzying mixture of Old French and Latin that, Einhorn says, was inspired by the macaronic (dual-language) motets that were popular during the medieval period. The libretto's words are accompanied by music that sounds at times as if it comes straight from a medieval manuscript and at others as if it were written in the 1920s.

It is, perhaps, this hybridity that makes Einhorn’s music so compelling as a complement to Dreyer’s film. Movies themselves — especially silent ones — are hybrid forms and collaborative products. They include elements from photography, theater, ballet, and pantomime, and they require huge teams of people for their creation and success.

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc,too, is composed of disparate elements. It is very much a product of its time, wearing the filmic techniques of the silent era on its sleeve (especially its iconic, long, close-ups of the intense Maria Falconetti’s face, head cocked to one side, tears streaming down her cheeks). Yet its provocatively sensual depictions of its heroine shocked critics of its time, earning it censure from Parisian clerics (among others); modern audiences may be more sympathetic to this most human portrayal of a canonic figure. And Dreyer drew on as many old documents as he could to reconstruct the trial that condemned Joan to death, rooting his ultramodern videographic essay in a history that stretched back some 500 years. His results were electrifying, and a screening that pairs these harrowing images with Einhorn’s dramatic score is sure to elicit thoughtful responses.

With an ancient story, an antique film, a historically informed style of presentation, and relatively new music, this performance offers a 21st-century audience the chance to take part in a constantly evolving collaborative artistic process.