In 1913 — on the precipice of the Great War’s countless horrors — Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring notoriously catalyzed a riot in a Parisian theater. By contrast, the San Francisco Symphony’s packed performance of this same work at Davies Hall this Saturday prompted one of the most immediate and unanimous standing ovations I have ever witnessed.

Now a staple of orchestra concerts, Stravinsky’s piece constituted the second half of this weekend’s program. The first half subsumed two works: Stravinsky’s Scherzo fantastique, followed by Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1. The whole first half seemed deliberately restrained, as though to reassure listeners who might otherwise be skeptical of The Rite to stay for the whole show.

Irrespective of the program’s intentions, all three pieces were far more enticing than off-putting.

Before the evening’s first notes resounded, I heard the man seated one row behind me whisper, “Oh, it’s a woman.” Whether he was referring to the conductor or the acting concertmaster was deliciously ambiguous. Similarly, at intermission, I stood behind two men who were criticizing the conductor’s gestures, tempos, and clothing. I wondered whether they would have been comparably critical if the conductor were a man (spoiler alert: The answer would likely have been a glaring “no”).

I wanted to write this piece without feeling compelled to mention that the evening’s world-renowned guest conductor, Susanna Mälkki, indeed happens to be a woman.

Perhaps particularly because I myself am likewise, I wanted not to be forced to mention it because I want to live in a world where gender (however defined) doesn’t matter. But I’m also achingly aware that this is not how the world writ large yet functions. And at the time of this writing, the smaller realm of conducting remains, fundamentally and egregiously, an old boys’ club.

In times when such things unfortunately must still be noted, therefore, let’s just go ahead and shout from proverbial mountaintops that Mälkki — a woman/person who first forged a successful career as a cellist before earning international esteem and awards including Musical America’s 2017 Conductor of the Year — led this weekend’s program like a boss.

Stravinsky’s Scherzo fantastique numbers among the composer’s earliest orchestral works. Like climbers on a cold mountain, the woodwinds were both tested and exposed in this work. Just as they did all evening, they easily summited the piece’s challenges.

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 is actually the third he wrote; it’s simply the first that was published. At the time (ca. 1795), Beethoven was establishing himself as a composer while still performing as an unforgettably daunting pianist.

In this piece, Beethoven masterfully assimilated Mozart’s grace, Haydn’s wit, and his own youthful (if perhaps overly) confident swagger. On Saturday, the Bay-Area-based Garrick Ohlsson courageously stepped into Beethoven’s shoes to perform the piano solo. Ohlsson conveyed all of the piece’s qualities with ease. For this weekend’s San Francisco audience, though, perhaps Beethoven’s swagger would have been better conveyed were Ohlsson to have swapped his tux for any tech-company hoodie.

The Concerto’s second movement foregrounds a solo clarinet alongside the piano. Carey Bell was superlatively deserving of a shout-out.

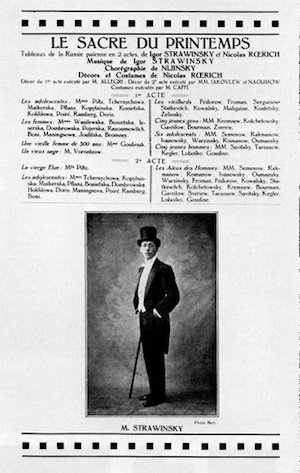

Even if you have never heard a full performance of Rite of Spring, excerpts are probably familiar due to Walt Disney’s Fantasia. Rite of Spring is in two parts: “The Adoration of the Earth” and “The Great Sacrifice.” Although the piece does not tell a specific story, the first part celebrates creative forces of Spring, whereas the second dramatizes a young virgin sacrificing herself to pagan gods.

During The Rite’s premiere, musicians struggled to understand the work’s idiosyncrasies, which include dissonant harmonies and deliberately displaced rhythms. But on Saturday, San Francisco Symphony handled this “modern” piece — now 105 years old — with masterful understanding. Moreover, in moments including the priceless gap between the music stopping and the audience monolithically rising to its feet, a badass woman named Susanna Mälkki wielded her suspended baton in a nameless space that she — singularly and securely — owns.