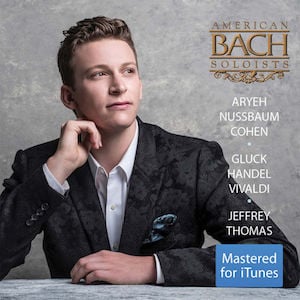

Now in his mid-20s, Brooklyn-born countertenor Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen continues to bound from success to success. The Metropolitan National Council Auditions winner, Adler Fellow, and Operalia finalist whose performance streamed on Medici-TV on Friday, July 26, has just released his first recital, Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen Sings Gluck, Handel, and Vivaldi, on the ABS Media label.

Without question, the recording, which is also available from various streaming services, shows Nussbaum Cohen as a complete artist with an impressive technique. Diction, phrasing, breath support, full rounded tone, and a flair for ornamentation — the veritable checklist of technical attributes essential to great Baroque singing — are there in spades. So is a total commitment to the swings between melancholy, despair, anguish, nobility, fury, pain, and love under duress at the core of the recital’s repertoire.

One of the most impressive features of Nussbaum Cohen’s artistry is tonal consistency as he moves (in the order chosen for the recital) from Handel’s great castrato/countertenor/mezzo showpiece from Rodelinda (1725), “Vivi, tiranno! Io t’ho scampato” (Live tyrant! I escaped you) to the slow, infinitely touching, legato singing of that opera’s “Pompe vane di morte! … “Dove sei, amato bene?” (The hollow splendor of death! … Where are you, dear beloved?). While the voice of one of his great predecessors, countertenor David Daniels, would tend to lose a bit of its glowing, pearly beauty and grow whiter under pressure, Nussbaum Cohen maintains tonal evenness throughout both arias. If, as is often the case with countertenors, his low tones are notably softer than his top, they are nonetheless rounded and quite beautiful.

One of the most impressive features of Nussbaum Cohen’s artistry is tonal consistency as he moves (in the order chosen for the recital) from Handel’s great castrato/countertenor/mezzo showpiece from Rodelinda (1725), “Vivi, tiranno! Io t’ho scampato” (Live tyrant! I escaped you) to the slow, infinitely touching, legato singing of that opera’s “Pompe vane di morte! … “Dove sei, amato bene?” (The hollow splendor of death! … Where are you, dear beloved?). While the voice of one of his great predecessors, countertenor David Daniels, would tend to lose a bit of its glowing, pearly beauty and grow whiter under pressure, Nussbaum Cohen maintains tonal evenness throughout both arias. If, as is often the case with countertenors, his low tones are notably softer than his top, they are nonetheless rounded and quite beautiful.

At this stage of the game, however, there are limitations. Having reviewed a good half dozen countertenor recordings of “Vivi, tiranno!” — with a live recital version by mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne with piano accompaniment thrown in for good measure — it must be said that no countertenor can come close to monster countertenor Franco Fagioli’s breathtaking vocal range and technique. As much as waiting for the high notes might be criticized as a shallow fascination with show, Baroque opera is ultimately a show that includes more than its fair share of virtuoso showpieces. Here, as in several of the other arias on the program, I kept waiting for the high notes that never came.

I also lament that instead of going deeper into despair in the recapitulation to Orfeo’s “Che faro senza Euridice?” (What shall I do without Eurydice?) from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), Nussbaum Cohen opts for a surfeit of lovely coloratura variations. Perhaps I should be struck dead by lightning on this very spot for saying so, but once you’ve heard the heartbreaking recordings of this aria by Kathleen Ferrier (live) and Maria Callas (studio), little else will suffice.

Ultimately, Nussbaum Cohen’s singing would be even more exciting if he were to risk sacrificing a bit of tonal homogenization in the process of abandoning himself more to the music. (In all fairness, that may in fact happen in live performance.) It will be exciting to discover if his voice opens up and expands in the next few years. Witness the mezzo phenomenon known as Cecilia Bartoli, whose range continued to expand upwards when she was Nussbaum Cohen’s age.

Conducting and playing by the American Bach Soloists period band, which includes many of the same players who distinguish Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, is superb. While it’s a plus that the instrumentalists are given two operatic Sinfonias by Vivaldi as a showcase all their own, it’s a shame that the less than inspired melody at the start of the second one, from La Verità in Cimento (1720), is so tediously repetitive.

The recording itself, captured in Belvedere’s St. Stephen’s Church by Andrés Villalta at the start of the year, excels in its synthesis of natural church resonance and clarity. If ABS ever finds the means to distribute its high-resolution (24-bit, 88.2kHz) files, you’ll find that they offer the best depiction of tonal and spatial depth. Otherwise, I’d opt for the CD over “Mastered for iTunes.” Hey, if you prefer file playback, you can always rip the disc to your computer in full CD quality rather than mp3.