Come for the music, go read the story

Why attend an operatic version of a short story? Perhaps you are hoping for an interestingly different perspective from your own imagined reading, or interested in how the music might augment the story, or looking for how innovative staging may do the same. Opera Parallèle’s production of Philip Glass’s In the Penal Colony at the Golden Bough Playhouse in Carmel this weekend offered a mixed bag of great musical performance with mediocre staging.

Glass’s opera is based on Franz Kafka’s short story of the same name. The story has only four characters, all male: an officer, a visitor, a soldier, and a prisoner. The prisoner has been detained for slipping up on the job, which is to salute his superior’s door on the hour, every hour. Without knowledge of his crime, the ability to defend himself, or knowledge of his punishment, he is sentenced to death by means of a torture apparatus managed by the officer. The apparatus is designed to inscribe the “commandment” which the convicted person has broken into their flesh, first on the skin, then, over the course of 12 hours, deeper and deeper into the convicted person’s body. Support for the use of the apparatus is dwindling in the penal colony and when the officer is unable to convince the visitor to publicize his observation of the apparatus in action, he believes it will fall into disuse. The officer releases the prisoner and kills himself using the apparatus, convinced that not using the apparatus would prevent him from meting out justice.

Rudolph Wurlitzer’s libretto stays close to Kafka’s text, mostly drawing from, reassigning, and rearranging dialogue from the short story. But, as the dialogue is the minority of the text, interesting elements such as hints about location, potential identity of the country in charge of the penal colony, and the camaraderie between the soldier and prisoner are dropped, the result is a thinner storyline with fewer themes.

Glass draws on his usual compositional techniques to move the story along, including his rhythmic “heartbeat” motive (a bass line on the beats with a tenor line pulsing at twice the bass-line rate), different rhythmic overlays on this motive, his trademarked arpeggios, scales, and occasional lyric moments. The heartbeat motive works especially well here. At times it underscores the internal anxiety and unease of the visitor as he listens to the officer describe the apparatus and contemplate how he will report on what he is observing. At other times, the motive suggests the motoric function of the apparatus, whirring cruelly along, augmented by canned mechanical sounds. Less successful was Glass’s melodic writing for the vocalists, which, when not in full-lyric mode was at times uninspiringly limp, like slightly heightened recitative: uneventfully pragmatic.

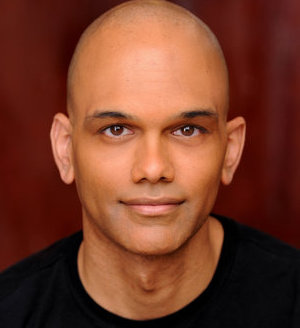

The instrumentalists of Opera Parallèle, Dan Flanagan, Ilana Blumberg Thomas, Jacob Hansen Joseph, Laura Gaynon, and Stan Poplin, indefatigably and movingly executed Glass’s score, and their intonation and ensemble work under the baton of Nicole Paiement were spot on. Vocalists Robert Orth and Javier Abreu were just as impressive, tightly locked with their instrumental colleagues, with beautiful tone and convincing acting (this latter point extended to Michael Mohammed and David Poznanter in their speaking roles). The acoustics of the Playhouse were less ideal and could have occasionally benefitted from better balance between unmiked vocalists and miked instrumentalists, with vocalists occasionally unintelligible.

Brian Staufenbiel’s staging and concept design were hit or miss. The use of projected visuals, which were occasionally animated, was often initially effective, but became overly simple and predictable. One effective use of visuals was when the officer’s drawings of the apparatus, when laid out on a table, were visible to the audience as a sketch above the singers, as though the officer were using a transparency machine. Another effective and beautiful moment resulted from the use of rotating stage space: a center circle and surrounding ring moving in opposite directions. During a moment of heightened anticipatory tension, the singers and actors stood still on the rotating areas, which resulted in elegant geometries accompanied by the pleasing regularity of Glass’s instrumental writing. But at other times performers were choreographed to move around busily on these rotations, drawing unartistic attention to the technology. The apparatus, so central to the story, was unfortunately unassuming and its demise at the end of the opera, cataclysmic in Kafka’s story, was almost dull on Staufenbiel’s stage.

If you came for Glass’s music, you were likely to leave the Playhouse pleased, if for a gripping multimedia experience of Kafka’s story, likely disappointed. Ultimately, Kafka’s storytelling was the most engaging element, usually effectively accompanied by Glass’s writing, spectacularly performed by Opera Parralèle. The opera opens a door into Kafka’s important work, with its themes of justice, intercultural interaction, definitions of masculinity, social change, and the power of privilege in naively unaware and dogmatically righteous forms. You may have missed a good musical performance, but the story was the best part.